It’s the dog days of April, in which principals of high schools inevitably must referee squabbles between teachers and students, impose discipline because of a school event in which students were drinking alcohol, or handle fights between students. These are the times that try a principal's soul!

It’s the dog days of April, in which principals of high schools inevitably must referee squabbles between teachers and students, impose discipline because of a school event in which students were drinking alcohol, or handle fights between students. These are the times that try a principal's soul!Still, April is also the time when principals can have a profoundly positive impact on the lives of these students and their families. Kids--even good kids-- are going to make bone-headed mistakes. Often in these cases, the principal must root through who did what to whom so that he or she can mete out school punishments justly, or provide parents with clear, accurate information. Here’s the rub: precisely HOW he or she roots out that information will be a determinative factor in how well the punishments are received by both parents and the students alike. It’s not easy.

After 15 years of being principal and making MANY mistakes along the way, I’ve learned there are a few guidelines that are helpful when ferreting out information from students. When I abide by these guidelines, families (more or less) respect my decisions and are willing to work with me.

1) Establish with students, up front, that if they tell the truth, the punishment will be lighter. I think it’s fundamentally important for kids to be truthful, and we ought to create incentives to act honestly. The flip side of this is we must be willing to punish those who lie with real severity, lest they conclude it's a better gamble to lie.

2) Second, be clear with them that you will NEVER ask them to betray confidences or give you names of those involved, unless someone is in IMMINENT danger. Most of the cases I had to become involved in were over things that had already happened, so there was no imminent danger. There was a case, however, of a suicidal kid who ran away from home and I knew that child had revealed her whereabouts to her best friend at school. I insisted with this child she betray that confidence, but also told her to tell her friend “that I made her tell”, so that it was my fault, not hers, to her peers. If we don’t ask for names, kids are generally willing to talk. A savvy principal, asking the right questions, can piece together what happened by comparing each kid's version of events.

3) In a judgment call between believing a student or not believing, err on the side of trust if the child has never lied before. A student's reputation ought to count for something, and this is a concrete way of telling kids that reputations DO matter. The worst thing we can do in these situations is accuse an innocent child. It hurts the kid and undermines us in the eyes of student body as someone not to be trusted. I tell kids that I’d rather trust them and be wrong than mistrust them and be wrong. However, I also say if I take them at their word and then catch them in a sure lie later on, that I would then no longer have a basis to believe what they told me earlier, and I will retro-actively impose discipline on the previous matter.

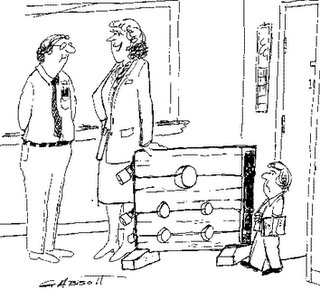

4) By asking “unexpected” questions, we can often tell quickly if they’re telling the truth. Two kids came late for school because "they went to breakfast together and the car broke down in the parking lot of the restaurant". I was suspicious. I put each child in a different room and asked them privately: “What did each of you have for breakfast?” That surprised them--it wasn't part of the story they rehearsed together, and it became immediately evident they were lying when the breakfasts didn't match. If you ask enough off the wall questions, sooner or later lies won’t hold up. (Then there was the opposite case of eight kids caught drinking before Prom who all came in privately and told me EXACTLY the same thing, down to the most specific detail. I was impressed by the intricacy of the story, but I also knew that they were lying—the truth is never that precise!) However, in the case where we truly don’t know (even if we suspect), it’s better to trust. As a practical matter, it’s going to be virtually impossible to have the parent support you as a principal unless you’ve uncovered more than “it’s unlikely your child is telling the truth”. Without the parent's support, you're not likely to have much impact.

5) In a similar vein, always trust the parents, unless there is evidence not to do so. Most parents, I believe, still want to do the right thing and most still tell the truth. Some do not, but we cannot allow these parents to prompt us to take a generally distrustful stance. “Parents are the primary educators”. This is as fundamental as it gets for Catholic educational philosophy, and our job is to assist these primary educators when raising their children. We cannot begin this partnership with the assumption that the parents are untrustworthy. Better to err on the side of trust!

6) Finally--and many principals will disagree with me on this--BECAUSE parents are the primary educators and because teaming with them is so important if the school's punishment is going to be effective with the kids, I meet with parents ahead of time, without the student present, and lay out what happened, and try to maneuver to common ground before I pronounce the school's punishment. That may mean, based on my read of the parents, that I temper what I had intended to do. I've decided during these meetings to make suspensions into Saturday school time, from three day suspensions to two day suspensions.

Controversial? Yep. But the principal's authority is not eroded if he or she privately decides to do something he or she had not intended. Yes, if a school matter, I can insist on a punishment that the parent may deem too "harsh", but I also know as soon as the parent leaves my office, my decision will be undercut, almost guaranteeing the child will grow less from the incident. And yes, there are times when we must insist on actions the parents simply won't support because the actions are severe and require a severe consequence. I've not had too many parents agree with me when I expel their child! But where we can reach common ground without compromising principle, I believe we should be willing to do so in order to speak as one voice to the child.

One last thing: Look carefully at school policy handbooks and how policies are crafted. I believe that parents expect us to handle their children individually and creatively, rather than bureaucratically. Do the policies of the school give principals this kind of flexibility? There is a huge difference between the phrase “students who do X will receive Y” vs. “students who do X are liable to receive Y”—one dictates to the principal what he or she must do, the other says what the principal may do, but gives the principal flexibility to do something lesser, dependent on the circumstances. We have a policy regarding drinking at school or school functions which says “Students who possess or are under the influence of alcohol at school or school functions are liable for expulsion”. This gives the principal tremendous clout, even while the principal has the flexibility to act creatively for the best interest of the child. May we do so with wisdom and patience!