I. The “dilemma” of academic diversity

Because we are an archdiocesan school, Montgomery Catholic is blessed by an extraordinary diversity of academic talent, ranging from students who are merit finalists to students who really struggle to achieve minimal course goals. With the exception of Math and English (which are tracked in an honors/non-honors sequence), all students attend classes together. Even within the tracked classes, there is a range of talent and ability.

Teachers, when designing an assessment, must make an impossible choice: Do we create a test that truly challenges our best and brightest, at the expense of our weakest? Or do we create an assessment that is “doable” for weaker students, but does not extend the top students? Faced with this choice, most teachers aim for the middle, where the negative effects on both groups are minimized, yet remain. Over the course of a 7th-12th grade curriculum, the effects of aiming for the middle are predictable: high achievers have college test scores that are not as high as they could be, and less able students have a VERY difficult time in the curriculum, as reflected in grade point averages which are lower than anyone wants.

II. Three ways to address:

There are only three ways that I know to address this dilemma substantially.

The first is to rigidly track students up and down the curriculum, allowing teachers to target each test to the class based on their ability. Without this article becoming a war over the pros and cons of tracking, suffice it to say tracking gives up a lot in terms of building a community of students, putting student leaders in a position to be leaders in their peer group (can we reasonably expect our good students to lead peers who they only know as acquaintances in the hallways?) and there’s at least some research that says tracking hurts the lower track students and doesn’t help the higher track. Besides, for us it’s a moot point, because we couldn’t do it anyway without re-structuring our program completely.

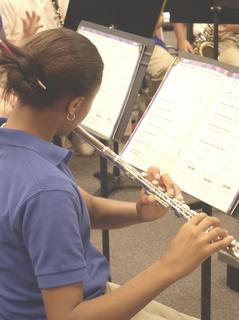

The second way is to give broad, open ended assessments which are graded on a rubric, instead of objective tests that are graded on a percentage. If, for example, I ask students to engage in a debate or perform a musical piece and grade this debate or performance on a 1 (low) and 4 (high) rubric, my less able students may work toward a 2+ or 3, whereas my top students could work to achieve the 4, without either group affecting the ability of the other to be successful. There are many web sites that assist teachers in developing such rubrics like this one which make our jobs easier. I believe we should give more of these kinds of assessments; they can often be exciting, interesting tools that significantly extend the “dryer” content of the class.

The second way is to give broad, open ended assessments which are graded on a rubric, instead of objective tests that are graded on a percentage. If, for example, I ask students to engage in a debate or perform a musical piece and grade this debate or performance on a 1 (low) and 4 (high) rubric, my less able students may work toward a 2+ or 3, whereas my top students could work to achieve the 4, without either group affecting the ability of the other to be successful. There are many web sites that assist teachers in developing such rubrics like this one which make our jobs easier. I believe we should give more of these kinds of assessments; they can often be exciting, interesting tools that significantly extend the “dryer” content of the class. Still, even teachers committed to giving these open ended assessments would agree that objective tests should be a standard part of the teacher’s assessment “arsenal”. What then?

III. Layered Assessments

The third way of handling academic diversity on tests is through what is often called a “layered assessment”. Though there are many ways to implement this idea, here’s how I would advocate we should do it at Montgomery Catholic:

Layer I: The first layer will be comprised of factual recall, translation and simple application problems and questions. Typically, this layer will comprise the bulk of the overall assessment. This layer is graded like any other test, by percentage correct (or by rubric). A student who scores less than 60% fails, between 60-69% a D, 70-79% a C, 80-89% a B. The only difference is a student cannot earn an "A" on this layer. Students may get up to a “B+” on this layer if they score 89% or higher.

Layer II: The second layer will be comprised of more advanced application problems, analysis or synthesis level questions. Successful completion of this level (70%+) adds a full letter grade (or 10 points, if scored numerically) to whatever is achieved in layer I. Thus to earn an “A” for the assessment, a student must receive a “B” on layer one, and pass layer II to increase their grade for the A.

If, in the opinion of the teacher, a student does reasonably well on layer II but does not pass it (for example, 50%), the teacher may award 5 bonus points to the overall layer one score, provided that this doesn't elevate the student's grade to an A. The only way to achieve an A is by successful completion of Layer II.

All students, then, should be required to attempt both levels, since it can only help them.

IV. Grading examples:

1. A student gets 73/90 on layer one (= 81%). So on level 1 he has a “B-”. He then scores a 7/10 on layer II, which means he has passed the second layer. This means the teacher adds one full letter grade to his B from layer I = A- for the overall assessment. The teacher records an “A-” (or a "91") in the grade book.

This works the same if the same teacher wanted to give an essay on either layer I or II, rather than grade by percentages. The teacher creates a rubric to determine if each essay is successfully completed. Whatever grade the layer one essay earns, if the student passes layer II, the overall grade is increased by one full letter grade.

2. A student gets 73/90 on layer one (=81%=B) as above, but gets 2/10 on layer two. The second layer isn’t successfully completed, so there’s neither a bonus nor a penalty; he receives a B- (or 81) for the assessment.

3. A student gets a 70/90 on layer I (=78%=C) and a 5/10 on layer II. Though he did not pass layer II, the teacher may give that student 5 points toward level I, which would elevate his layer I score to an 83 (=B). In effect, the layer II acts as a "bonus" question here.

4. A student gets a 90/90 on level I. He has a B+ so far. If he passes layer II he will receive a full letter grade bump to an A+. If not, he has a B+.

5. Typically, a student who does poorly on layer I will likely do poorly on layer II. Nevertheless, the same principles apply: A student who fails level I but passes level II gets a letter grade bump from an “F” to a “D”.

V. Benefits of a Layered Assessment:

The layered assessment is an attempt to challenge the top tier students with meaningful, challenging extensions of class material, so that over the course of their 6 years at MCPS, they will be able to think at higher levels. We believe this will translate into higher ACT, PSAT and SAT scores for college.

At the same time, the layering aids less able students grade-wise. Since the higher level questions are bracketed in layer II, these questions do not hurt the weaker students’ ability to get as high as a B on the test. A traditional test which contains 10-20% of “A-level” questions (that a weaker student is less likely to successfully complete) significantly narrows the window of success for less able students; they must get a high percentage of every other question correct to pass.

Also, by labeling the questions clearly as “level I” or “level II”, the teacher helps the weaker student by identifying those questions which gives him the most chance of success. (Sometimes, weaker students will spend too much time on questions that are beyond their scope.)

In some cases, the stronger student benefits grade-wise from this system, too, by giving him more margin for error in obtaining an “A”. In a traditional system, to achieve an A, the student must get just about every question right, or “92%+. But using the layers, a student may miss a few “layer one” questions and still be able to achieve an A. In the grading example from # 1 above, by way of illustration, if the student were graded traditionally, he’d have an 80% (73/90 + 7/10) or a B. But in the layered system, he would have an A.

Everybody wins.